When Immanuel Lanzaderas first began working at a law firm, it was impossible not to feel the culture shock. “You walk into a private firm in this city and there’s a really stark contrast to what you see on the subway or in the city,” he says. Lanzaderas is a Filipino-Canadian who grew up on social assistance in a suburb of Toronto. When he joined a boutique labour firm in Toronto, just four of the 35-odd lawyers were visible minorities — not a terrible ratio for a law firm, but wildly disproportionate in a city where nearly half of the population is comprised of ethnic minorities.

Lanzaderas is a good talker and a personable guy, but when it came to networking at the office he often found himself at a loss. “I learned that there were whole modes of speaking and topics of conversation that I just couldn’t participate in,” he says. Lanzaderas would stand silent while lawyers talked about hockey or golf, the cottage or private school. When colleagues found out Lanzaderas’s background, their response was often, “Oh, our nanny is Filipino.”

Lanzaderas is a good talker and a personable guy, but when it came to networking at the office he often found himself at a loss. “I learned that there were whole modes of speaking and topics of conversation that I just couldn’t participate in,” he says. Lanzaderas would stand silent while lawyers talked about hockey or golf, the cottage or private school. When colleagues found out Lanzaderas’s background, their response was often, “Oh, our nanny is Filipino.”

After just three years, Lanzaderas walked away from his job. Today he works for Legal Aid Ontario, an opportunity that pays less but better suits his lifestyle and includes a more multicultural working environment. Lanzaderas says being a lawyer in a virtually all-white office was mentally trying in ways he hadn’t anticipated — ways the firm had surely never even considered. “It’s like being in a room with a loud furnace,” he says. “Sometimes you don’t notice the hum. But after a certain point it gets really annoying, and you just need to leave.”

Lanzaderas’s experience isn’t unique. Law firms across Canada have a problem with diversity. While many run equity initiatives and committees designed to attract diverse articling students and associates, they don’t have a great track record when it comes to retaining them. Today, with clients looking more closely at a firm’s demographics and with an increase in the diversity of law students, the push is on for firms to get it together. If not, they could miss out on a growing pool of talented young lawyers as well as business opportunities.

Law firms aren’t like other workplaces. Good national numbers are hard to find because in Canada, unlike in the U.S., firms aren’t required to report their hiring demographics. The numbers we do have, however, paint a clear picture. While other prestigious professions that were once predominantly white have made huge strides, law continues to lag behind. A report from the Law Society of Upper Canada drawn from 2006 census data found that, though almost a third of Ontario doctors and engineers were visible minorities, only 11.5 percent of lawyers were from an ethnic background. The ratio remains similarly low across the country.

On one level, the obstacles appear during the interview process. In its 2011 report on articling placements in Ontario, the LSUC found that 28 percent of the students who did not land articling positions self-identified as coming from a racialized community. But the barriers for minorities don’t just appear when law grads decide to join a firm. They can exist to varying degrees at different levels over a lifetime — from primary school to university. Hadiya Roderique, an associate at Rubin Thomlinson LLP and the treasurer of the Canadian Association of Black Lawyers, got used to being the only black person in the room when she studied psychology at McGill University. At the University of Toronto’s law school, she was one of four black students in a class of 190, and when she ended up on Bay Street it was not that different. She believes there are not enough talented young people from a mixture of backgrounds in the pipeline. “I think we have to get more minority youngsters graduating high school and then into law school.”

And of the relatively small number of racialized lawyers who do get hired, many don’t stick around. According to a recent report from Ryerson University, while visible minorities comprise 14.4 percent of all lawyers in the Greater Toronto Area, they only account for 6.8 percent of industry leaders, including judges, partners and Crown attorneys. “There is a problem with attrition,” says Jason Leung, director at Ridout & Maybee LLP and the northeast regional governor of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association.

“Firms may embrace the benefits of diversity at lower levels, but they don’t seem to follow through at the partnership or leadership level.”

Minority lawyers’ earnings reflect this. According to the LSUC report, the mean annual earnings of racialized lawyers in 2005 in Ontario was $101,800, compared to $176,100 for white lawyers. The report reached a scathing conclusion: “These findings suggest the systemic exclusion of racialized lawyers from higher paying positions.”

The reasons for this are more complex than simply a case of white, upper-tier partners conspiring to keep out other groups. Immigrants whose first language isn’t English may have a hard time gaining credibility in a profession where an accent can be misinterpreted as a language problem. Some young lawyers may shy away from big downtown firms, scared off by horror stories of the old boys’ club, and find themselves drawn into opportunities at smaller firms, in-house counsel jobs or the public sector.

And then there are lawyers who join a firm and, like Immanuel Lanzaderas, find that they just don’t fit in enough to see a future. Dal Bhathal, who runs legal recruitment company The Counsel Network and is a board member of the South Asian Bar Association of Toronto, says she’s seen many young South Asian lawyers leave big firms. “I think some young lawyers used to feel that to make it in a large law firm you had to have the right connections,” she says. “Your parents had to be in a social circle where they knew CFOs and their clients, and so on. If you didn’t have connections to that particular social group, it was difficult to advance.” If you feel you’ll never make partner and have little to say to your colleagues around the water cooler, why stick around?

Most top firms know the system is working against racialized young lawyers and, to their credit, they’re trying to change things with diversity initiatives. Their motivation isn’t simply to create social justice; it’s a response to real economic imperatives. Starting in the early 2000s, big corporations began asking their legal counsel tough questions about diversity.

“We were looking south of the border and noticing a marked uptick in the United States in interest about diversity,” says Kate Broer, a partner at Fraser Milner Casgrain LLP who is in charge of the firm’s diversity programs. “Clients from the United States were asking more questions. ‘Who are the people on your files? What is their background?’” That pressure has only grown. In a recent poll of members of the Association of Corporate Counsel, more than half of Canadian general counsel say they consider a law firm’s diversity policies when they are retaining outside lawyers.

Firms are discovering that the homogenous group of male leaders that might have been successful in past decades has its limitations in the twenty-first century. “There is a business case to be made for having a diverse workforce,” says Jeff Fung, CEO of MyLawBid.com and former vice-president (fundraising) of the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers. “It helps increase the different perspectives that firms might have. It’s also good for business development to expand into new markets. In particular, having language diversity can’t hurt in accessing the different ethnic communities in Canada.”

Firms are also doing the math at the recruitment level. As Canada’s ethnic makeup changes, firms that only draw in young lawyers from select backgrounds are missing out on a large and gifted talent pool. Meanwhile, today’s students are assessing diversity when they are choosing where to apply. “When I meet students, I will get questions like: ‘How many LGBT lawyers do you have at your firm?’ ‘How many black lawyers?’” says Janene Charles, director of student programs for Stikeman Elliott LLP. “They want employers that align with their needs and their moral compass.”

The most effective diversity programs at Canadian firms are multifaceted and tackle outreach, youth, recruitment, retention and business development. Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP supports Law in Action Within Schools (LAWS), a program run by U of T law school and the Toronto District School Board that educates youth in inner-city high schools about the law and the profession. “If a law firm can do anything, it’s to get out there and make this an accessible profession,” says Mary Jackson, chief officer, professional resources.

Stikemans has brought in a cross-cultural coach to run group sessions, its new hires receive diversity training and its student mentorship program takes both gender and racial diversity into account when matching people up.

And FMC holds training sessions for staff on topics such as unconscious bias. “The sessions are primarily targeted at our leaders, to deconstruct and examine the unconscious biases that we all have and to help us be better when we make decisions,” says Broer. She says the program has triggered conversations that never existed before, but admits that recruitment is still a challenge for FMC. “The reality is, there are things we’re still working on to do better,” says Broer. “One of the things we need to do longer term is improve our representation.”

Canadian firms with the most successful diversity initiatives recognize that they need dynamic programs that are accountable to upper management, and not merely public relations statements or strategic hiring policies with no follow-through.

“Just issuing positive statements about diversity doesn’t work,” says Joy Casey, founder of A Call to Action Canada, a national non-profit initiative aimed at creating better diversity — including racial — at Canadian firms by asking in-house counsel at major companies to consider diversity when hiring law firms. “We can’t just say, ‘Oh well, eventually if we have enough at the lower level they’ll work their way up.’ That hasn’t happened for women and it’s not happening for visible minorities.”

But others observing the profession’s diversity record are feeling hopeful. Bhathal says that over her 15 years in the business she has seen many promising changes, including a rise in the number of lawyers from a mix of backgrounds finding their way to law firms and staying. “It’s still early days,” she says. “Law firms are still trying to figure out what they’re doing. I think they’re just becoming aware that it’s positive to have a diverse work force. How that translates into action is the next issue.”

This story is from the 2012 edition of PrecedentJD Magazine

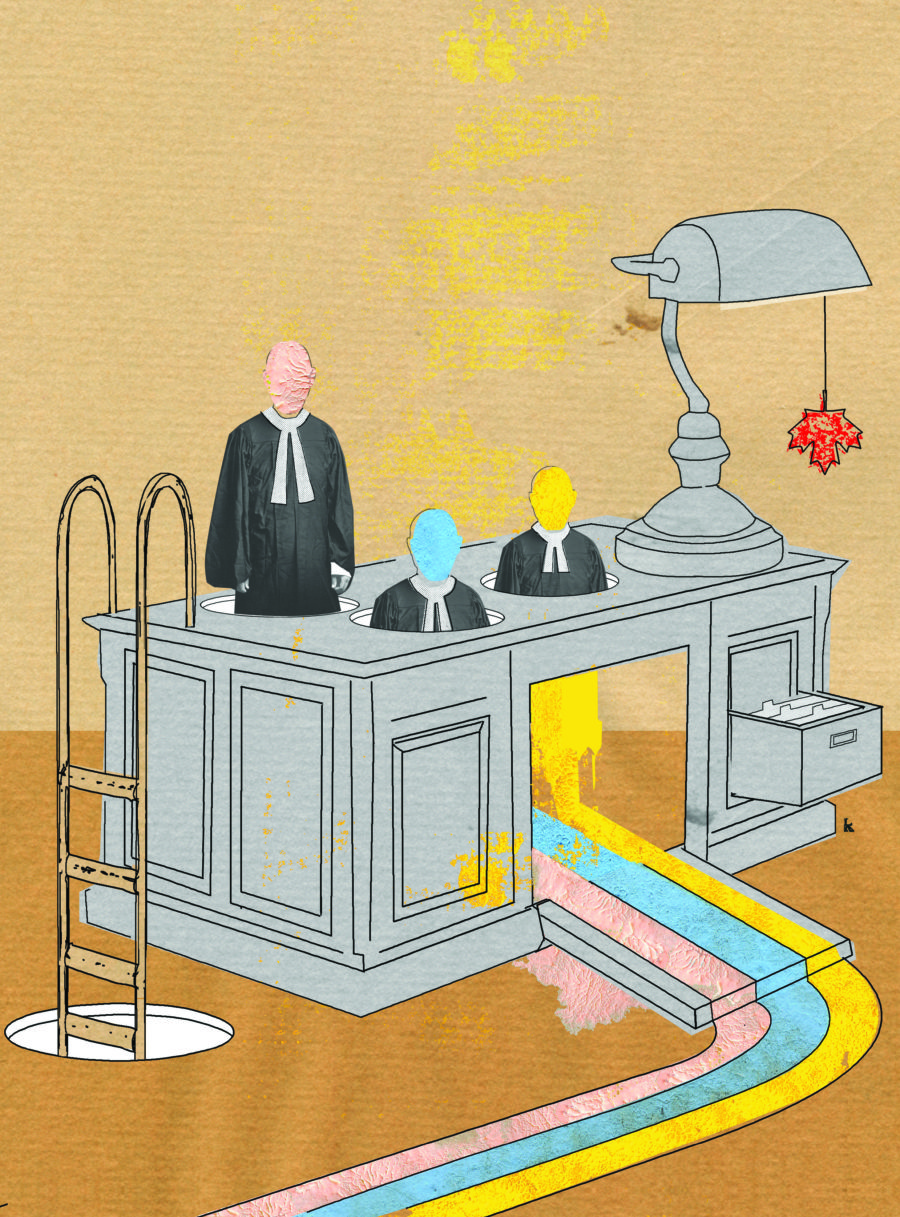

Illustration by Katy Lemay